When Students Can't Go Online

Nearly every school in America has some form of Internet connectivity—but that alone doesn't mean all kids have equal access to the web.

Tim Berners-Lee, the British scientist credited with the creation of the Internet, insists that access to the World Wide Web should be recognized as a basic human right. Using that logic, if education is, as the UN states, "a passport to human development," then Internet access is a right that should be extended to all schools. In America, that goal has largely been achieved.

Currently, 99 percent of America's K-12 public schools and libraries are somehow connected to the web, in large part thanks to the Federal Communications Commission's congressionally mandated "E-Rate" program, which went into effect in 1998.

However, while that progress deserves merit, merely having some sort of Internet connection is an outdated standard. After all, that 99-percent statistic was achieved in 2006. Technology is integral to the modern learning experience, whether it’s as simple as a basic wi-i or as advanced as the artificially intelligent software that's replacing textbooks. In today's schools, having a dial-up connection is far from sufficient when measuring adaptation to modern times.

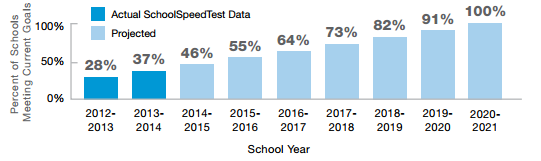

In June 2013, President Obama announced his ConnectED initiative, which aims to equip practically every school in the country with a high-speed broadband connection within five years. Late last year the FCC approved an additional $1.5 billion in funding for the E-Rate program, bringing its total annual budget to $3.9 billion. According to the administration, a typical school has about the same connection speed as the average American home but serves about 200 times as many users. Some schools even have to ration out Internet time to students.

EducationSuperHighway, a nonprofit that evaluates school broadband speeds, says that situation leaves a lot of room for improvement. Around the same time that Obama announced his initiative, the organization launched an online tool dubbed the "SchoolSpeedTest" which essentially measures Internet capability at schools across the nation. The results showed that, given the current rate of efforts to get schools connected to high-speed Internet, Obama's five-year plan may be wishful thinking.

Technology's integration into nearly all aspects of education has made Internet connectivity, whether at home or school, essential for kids. Any student without access—namely connectivity that's sufficiently fast—inevitably falls behind. While in the recent past having Internet access might have been necessary strictly for research purposes, these days many home assignments can only be completed via online software.

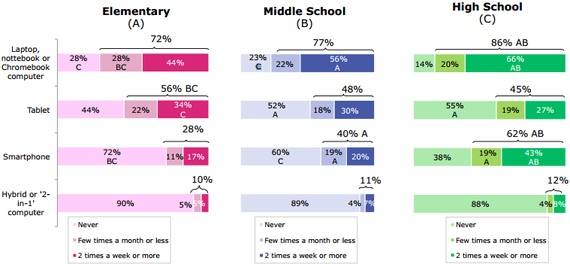

The devices typically used to complete schoolwork vary greatly by factors such as students' grade level:

The chart above reflects the results of Pearson's 2014 "Student Mobile Device Survey," a national study that looked not only at the usage of certain devices but also at users' attitudes and preferences, among a host of other ed-tech topics. It even explored how different demographics respond to technology's impact on education:

- Students whose parents graduated from college or graduate school (a proxy for higher socioeconomic status) are much more likely to report regularly using tablets than their peers whose parents didn't attend or complete college (59 percent, 47 percent, and 51 percent, respectively).

- African American students appear to be the most optimistic about the impact tablets will have on the classroom. They are more likely than both their white and Hispanic counterparts to agree that tablets will change the way students learn in the future (96 percent, 90 percent, and 88 percent, respectively).

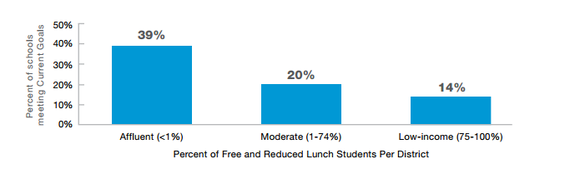

But as technology morphs from being a luxury to being a necessity, the chasm between the performance of low-income students and their more affluent peers is coming under even greater scrutiny. Advocates say the tech movement is further exacerbating the already-large achievement gap; in education circles, this phenomenon is dubbed the "connectivity gap" or the "digital divide." Discrepancies exist among schools and across districts, but they also spread to individual students, many of whom live in homes without sufficient connectivity.

Some districts have adopted creative ways of overcoming this problem. In California's high-poverty Coachella Valley district, for example, school buses are being outfitted with wi-fi hotspots and placed in nearby trailer parks so students can have access outside of the classroom. Washington state's Kent School District, which serves a large refugee population, is installing wi-fi kiosks in public-housing developments so students and their parents can get online.

Still, these efforts are little more than stopgaps. As research shows, lower-income schools are still lagging far behind in the race to get on the high-speed grid:

Percentage of Schools in the U.S. Achieving Current Connectivity Goals by Family Income

But the digital divide isn't limited to Internet access, according to Karen Cator, who oversees Digital Promise, a congress-affiliated research organization. "Even if they have access, they need to know how [to use the web]," she told me. "And if they are digitally literate, it's then engaging students in the power of using technology so they can be better learners."

Of course, poverty isn't intrinsically linked to digital illiteracy—but for various reasons the two factors are closely related. Meanwhile, being tech savvy alone doesn't mean a student automatically has digital literacy when it comes to using technology for learning.

According to the 2012 Pew report “Digital Differences,” only 62 percent of people in households making less than $30,000 a year used the Internet, while the usage rate among families making between $50,000 and $74,999 was at 90 percent. Teachers who educated low-income students tended to report more obstacles to using educational technology effectively in their classrooms than their counterparts in more affluent schools, according to a survey included in the report.

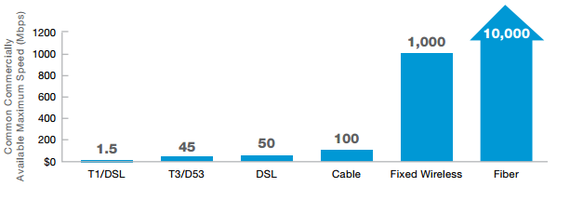

As the nation continues to navigate the shift from dial-up to broadband, there is a growing sense that this transition alone won't be enough to close the divide. Many ed-tech experts have, in turn, advocated for the installation of fiber networks at schools as key to helping level the playing field. According to a recent FCC report, about 41 percent of rural schools and 31 percent of urban ones lack fiber network connections.

Fiber is the highest-capacity broadband technology available today, and according to Evan Marwell, who runs EducationSuperHighway, it's the best option for most schools. "Fiber is the only technology that can deliver the kind of capacity that a school would need to have. We need to get Fiber in every school."

While the underlying merits of technology as a learning tool are still heavily debated, it's clear that having it in some capacity is better than nothing at all. For example, adequate technology allows for practices like "differentiation"—ed-speak for personalized learning experiences that allow each student to work at his or her own pace. In traditional classrooms, differentiation can be extraordinarily difficult for teachers to implement given how diverse their students are. Kids with different backgrounds, abilities, and learning styles are often arbitrarily lumped together, forcing educators to "teach to the middle."

This widespread challenge demonstrates the importance of high-speed connectivity at schools. Adaptive learning materials—software that in an instant can assess the individual needs of each kids in a classroom—can help teachers differentiate, freeing them up to actually concentrate their students and respond to their needs.

"The most important point is that today, in order to be a learner ... you must have access to the Internet," Cator said. "We need to make sure that people have the right access when and where they need to learn."